Radoslav Angelov

Junior Judge at District Court of Lovech

INTRODUCTION

“Can the judge presides over court proceedings according to his oath, however against the law?” – asked. lawyer V. Braykov in his study of the modern administration of justice through the crystal prism of his historical-philosophical view of conscience, moral duty and justice of judges (Braykov, 2014).

“Can the judge presides over court proceedings according to his oath, however against the law?” – asked. lawyer V. Braykov in his study of the modern administration of justice through the crystal prism of his historical-philosophical view of conscience, moral duty and justice of judges (Braykov, 2014).

What is the oath every magistrate takes? Does it make difference – as an element of the complex factual composition of the law, or as a new framework of our own moral and ethical values? Through the words of the oath, can we perceive the time and way of thinking of our colleagues back in the history of the Bulgarian judicial system?

The latter and many other questions inspired this study.

According to Jeremy Cooper, the[1] (UNODC, 2018) oath is a source of judicial ethics and professional conduct. Oath is a performative speech act arranged in a certain logical sense, which the profession in question is obliged to observe and perform with regard to its objectives and functions. In the area of the administration of justice, the oath is more often than not encountered in the statutes of the relevant professional organisations (unions, associations of judges or prosecutors) or in the ethical rules of the professions concerned (judge, prosecutor, investigator) in a specific country. Thus oaths should be classified as part of national law (source of domestic law). Due to the fact that the oath is placed in the structural law, it acts for a normative source of law. However, from it we cannot draw a general, conditional and abstract rule of conduct with a fixed penalty, which is why I am rather inclined to assume that an oath represents a negative source of law. The oath has an idealistic and solemn character, and its sacred making is a sign that the incoming magistrate is solidarized with the common goals, ideas and views of the professional community. Thus, an oath may be classified as a public promise by a person who does perform or does not perform certain acts, a unilateral contract the performance of which is aimed at all persons. It resembles the legal principle rather than the rule of law. Therefore, the oath has subsidiary nature. It is common in practice to take an oath upon getting a respective judicial position by repeating the words of the head of the magistracy who reads the oath, or by reading the oath directly from the sworn list. In both cases, the incoming person is obliged to to sign the text on this sheet. Therefore, the oath also has a written form, which distinguishes it from unwritten sources of law, such as principles, customs and the judicial precedent. In summary, the oath is a normative, specific source, which has an oral and a written form, and by its legal nature is a unilateral deal – a public promise of compliance with the law and carrying out duties to increase confidence in the authority of the judiciary. The violation of the public promise is attached to a sanction, which is a moral and a social one rather than a legal one. This is true because only the violation of the code of conduct of ethics is a ground for dismissal, but this does not apply for the violation of the oath. The Code of Ethics does not contain provisions governing public relations on the occasion of the oath. The above convincingly substantiates the assessment of the magistrate’s oath as an important normative source of national law as far as judicial ethics and professional conduct is concerned.

HISTORY OF THE OATH IN BULGARIA

The present study aims to present the contents of the oath of the magistrate from the Liberation of 1878 until now (4.7.2023).

The following acts are used as normative sources:

- Temporary Rules for the Settlement of the Courts in Bulgaria, issued by Prince Alexander Dondukov on 24 August 1878 in Plovdiv, which largely reproduced the Law on the Judicial Structure of the Russian Empire of 1864 (Gabrovo, 2016). The provisional rules were in force until the adoption of the first Bulgarian Law on the Establishment of Courts on 25.05.1880 (State Gazette No 52 of 14 June 1880).

- The Court Order Act (COA) of 1880 (promulgated in State Gazette No 47 of 02.06.1880), which applied to Eastern Rumelia since 1 January 1886. The clause was adopted at a later time and promulgated in State Gazette No 52 of 14 June 1880, as an addition to Article 102 of the Act.

- The Court Order Act of 1899 (promulgated in SG No 7 of 12 January 1899), the effect of which covers all the territories of United Bulgaria. The oath was updated by the Amendment to the Act in SG No 95 of 5.5.1910.

- The Court Order Act of 1934 (Prom. SG No 182 of 12.11.1934). The oath was promulgated in the Act in State Gazette No 83 of 16.8.1935.

- The Court Order Act of 1948 (Prom. SG No 70 of 26 March 1948) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act 1948 (prom. SG No 70 of 26.3.1948)

- The Court Order Act of 1952 (Prom. SG No 92 of 7.11.1952) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act of 1952 (prom. SG No 92 of 7.11.1952),

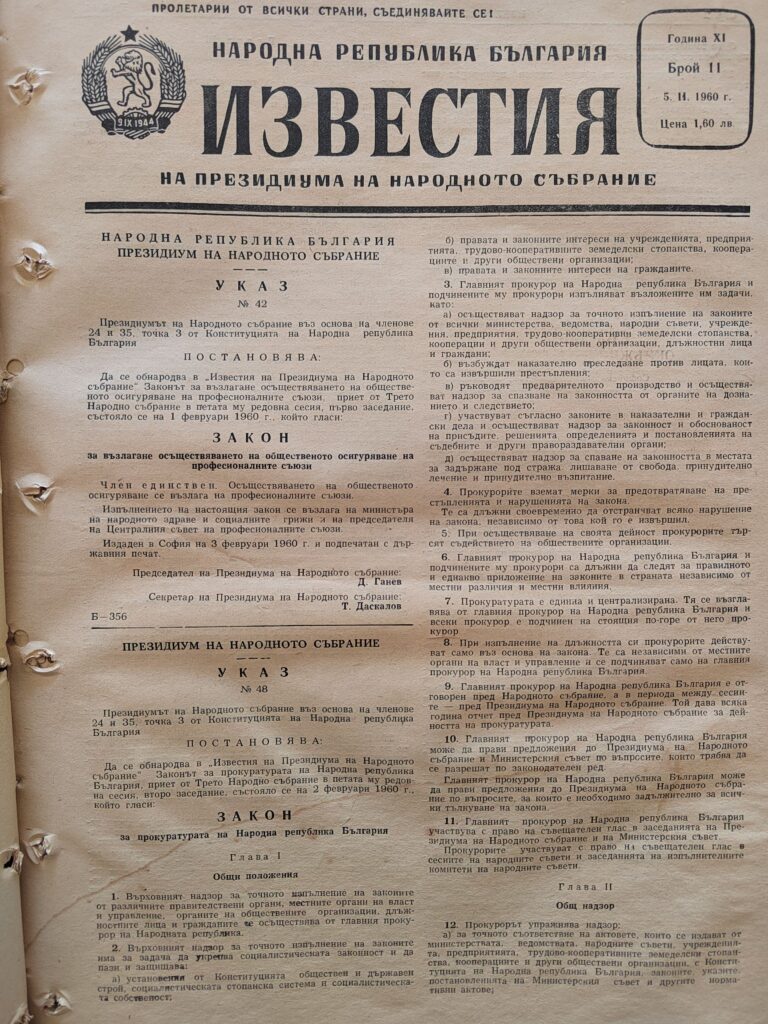

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office Act of 1960 (prom. SG No 11 of 5.11.1960)

- The Court Order Act of 1976 (prom. SG No 23 of 19 March1976) and the Rules on the organisation of the work of regional, regional and military courts (promulgated in SG No 89 of 15.11.1977).

- The Prosecutor’s Office Act of 1980 (prom. SG No 87 of 11.11.1980 )

- The Judiciary Act of 1994 (published. SG No 59of 7.1994)

- The Judiciary Act of 2007 (prom. SG No 64 of 7August 2007 )

It should be noted that the oaths of magistrates are not always accepted alongside with the basic statute law. For example: The oath under the Court Order Act 1976 is described in the Rules of Courts promulgated in 1977 (SG No 89 of 15.11.1977). Oaths under other laws were created at a later point in time by the Act amending and supplementing the law. For example: The Act on the Settlement of Courts of 1880 was promulgated in State Gazette No 47 of 02.06.1880, and the Act adopted an oath, which was promulgated in State Gazette No 52 of 14 June 1880; and under the 1934 Act, the oath was adopted only in the Act of 1935 (SG No 83 of 16.8.1935). In the history of the Bulgarian magistrate’s oath, there is also an example of an amended one: under the Order of Courts Act of 1899, it was amended by the Act (SG No 95 of 5.5.1910), replacing “His Royal Highness The Prince” with the words “His Highness the King of the Bulgarians” and the word “principal” is replaced by the word “kingdom”. In addition, the digital provision of the oath from Articles 32-135 has been changed to Articles 44-147.

For easier presentation, as an element of the identification of the oath, we will present the year when the relevant statute law of the judiciary was promulgated, rather than its amendment or adoption of a secondary act.

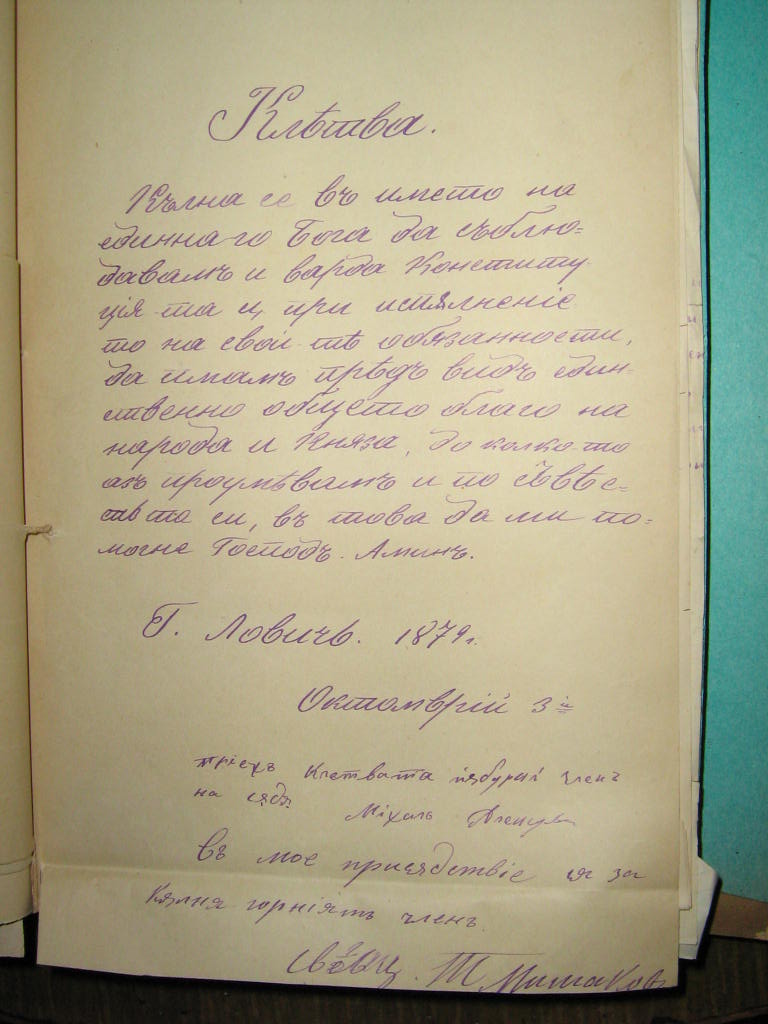

The sworn list, written by priest Todor Mishakov – Chairman and First Judge of the Lovech District Court since 03.10.1879, can be used as a historical source of the 1879 Clause. For the rest of the oaths we have used publications from the State Gazette.

When quoting, the author used the APA Sixth Edition standard.

CONTENT AND ANALYSIS OF OATHS

After each Basic Law, new statutes for the judiciary were adopted, the content of which increased in volume. If in the first laws the oath was at the beginning, with the passage of time its text would be moved to the middle or to the end of the law.

On the interactive figure presented below, you can see the comparison between the forms of government that the Third Bulgarian State has over the years and the respective statutes of judicial law.

When you press the corresponding structural law, a column opens on the left. This column presents the oath through a photograph from the State Gazette, an adapted text version of its content and a brief commentary.

Interactive image

Oath 1879

CONTENT OF THE OATH:

The affidavit, written by priest Todor Mishakov – Chairman and First Judge of the Lovech District Court since 03.10.1879, can be used as a historical source for the 1879 Clause.

I swore, in the name of the One God, to observe and defend the Constitution and in the fulfillment of my duties, to consider only the common good of the people and the prince, as long as I understand, even in my conscience, that the Lord may help me. Amen.

Todor Mishakov – President and First Judge of Lovech District Court since 03.10.1879.

NOTES:

From the content of the oath of 1879 one can draw a conclusion about the connection of Bulgarian justice with the Christian values – trust in God, conscience, dignity, good for the community, which has its own logical explanation. The oath was adopted by the Russian Organic Law of the Courts of 1864, when the St. Petersburg Palace paid tribute to the church. The oath was formulated immediately after the Liberation of Bulgaria, associated with the protection of the Slavic peoples and their common language and religious faith. In addition, the hostilities were carried out under the protection of battle flags consecrated by the Orthodox Church with depicted saints on them. In addition, the main accumulator of the Bulgarian liberation idea were the struggles for an independent church, the church and cell schools, the activities of the Bulgarian Revivalists – Paisii Hilendarski, Sofronii Vrachanski, Hristaki Pavlovich, Petar Beron, Vasil Aprilov and others. The San Stefano Peace Treaty reproduced the geographical boundaries of the Bulgarian diocese, i.e. the territories in which there was a compact Bulgarian population ready for consolidation of an independent state. Therefore, in the period after the Liberation, the oath was related to the faith, which reproduced the ideal of the Bulgarian Revival Bulgarian, his history and national identity. The end of the oath... in helping me God. Amen" gives it a symbolic sound of a prayer.

Oath 1880

EXTRAXT FROM THE LAW:

Annex to Article 102 of the Law

The oath the judge takes when he takes office.

I promise, and I swear by the name of the Almighty God, on his holy gospel and on the life-giving Cross of the Lord, to be faithful to His Highness the Bulgarian Prince, to perform holy and relentlessly the Constitution and the laws of the Principality, to judge in a clear conscience without any personality for the benefit of anyone, and to do in all things as required by the vocation in which I enter, remembering that I will account for everything before the law and God of the Last Judgement.

As a certificate of this, I kiss the word and cross of the Savior. It’s Amin.

Annex to Article 46 of the Law

An oath to be taken by the bailiff when he takes office.

I promise and swear in the name of the Almighty God, before his holy gospel and before the living Cross of the Lord, to be faithful to His Highness the Bulgarian Prince, to perform holy and relentlessly theConstitution, to perform honestly and in good faith all the duties of the service which I am charged with, and all the rules and laws, orders and orders that are relevant to this commitment, not to exceed the power which I have been given, and not to cause harm to anyone with intent, but on the contrary to defend all the interests entrusted to me as my own, remembering that I am obliged to respond to all things before the law and to the God of the Last Judgment.

As a certificate of this, I kiss the Word and Cross of my Savior, Amen.

Annex to Article 20 of the Interim Judicial Rules

The juror’s oath:

I promise and swear in the name of God Almighty, before His Holy Gospel and the Living Cross of the Lord, that in the work for which I have been chosen, as a Judge, I will put all my strength as far as my mind can be, to meticulously examine both the circumstances which incriminate the defendant, as well as the circumstances justifying him, and that I will give the decisive voice, according to him, what I hear and see in the Court, according to the same righteousness and the conviction of my conscience, by not acquitting the guilty, and not condemning the innocent, remembering that I am obliged to give an answer to all this before the Law and the Dreadful Judgment of the Lord.

NOTES:

We find more information about the 1880s in the Annual Collection of Laws of the Bulgarian Principality, S. 1886, p. 117; published in State Gazette No 52 of 14 June 1880, the link between secular justice and the spiritual beginning of the post-liberation Bulgarian continued to be maintained. In the oath again there were notions related to the faith of man. But unlike the oath of 1879, the judge took an oath to execute the Constitution and the laws of the Principality, which is proof of the existence of national self-confidence of the magistrate, the restored statehood, the pride of the own laws created by the liberated Bulgarian. Thus, along with the motive of the previous oath of connection between the judge and God, the new oath introduced the principle of the legality of the Bulgarian state, rather than laws that were made up of a foreign military-political power. The use of the term “vocation” is evidence that the magistrate was perceived as a profession with a high sense of morality and duty. Unlike the previous oath, the oath of 1880 also introduced a penalty section – in case of non-observance it was held liable under the law and before the Last Court. Therefore, since 1880, the oath of the magistrate was not only a moral character and solemn element, but also a legal obligation, since the failure to comply with it led to sanctions: secular – responsibility according to laws, and spiritual – before the Last Judgment. Again, the oath had the structure of prayer, as it ended with kissing the Bible, the Cross, and the word Amen.

Oath 1899

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

CHAPTER XIV.

For the oath.

132. Every judge or prosecutor shall, upon entering the service, take the following oath:

“I promise and swear in the name of God Almighty God to be faithful to His Royal Highness the Prince, to perform holy and inviolable laws of principality, to judge with a pure conscience, without every bias and personality, to keep holy the mystery of meetings, and to do in all things as an honest, good and just judge, remembering that I will give account to the law and to God.” Amin.

133. Notaries, secretaries, sub-secretaries, bailiffs and candidates for judicial office shall, upon entering the service, take the following oath:

“I swore by the name of God that I would be faithful to His Clerical Highness of the Bulgarian Prince, to keep holy and inviolable the laws of the principality, to perform honestly and conscientiously the duties of the service entrusted to me, and all the rules, orders and commands that apply to me, do not exceed the authority that has been given to me, and do not intentionally cause harm and loss to anyone, to keep secrets of the deeds which are entrusted to me and ordered to perform in the circle of my duties, remembering that I am obliged to give account of all things before the law and before God. Amin.

145. The officials listed in the previous members shall be sworn in before the general meeting of the court to which they are appointed.

146. If the appointed official of the judicial office refuses to take the oath established above, he shall be deemed not to have accepted the post.

The Amendment(SG No 95 of 5.5.1910) to the Order of Courts Act of 1899 was amended by, replacing “His Royal Highness Prince” with the words “His Highness of the Bulgarians” and the word “the Principality” shall be replaced by the word “kingdom”. In addition, the digital provision of the oath from Articles 32-135 has been changed to Articles 44-147.

NOTES:

The oath of 1899 was the same for judges and prosecutors. It is different in content from that of notaries, secretaries, sub-secretaries, bailiffs, candidates for judicial posts when they enter the service. The oath was also subject to a legislative amendment by the Act (SG 95 of 5.5.1910). The difference between the original and the amended version of the text of the law is to the amendment of the expression “His Royal Highness Prince” with the words “His Highness the King of the Bulgarians” and the word “Prince” is replaced by the word “kingdom”. There was also a change in the digital provision of the oath in Art. 132-135, in Art. 144-147. The amendment of the law is the result of the change from principality to kingdom, which is why it does not in essence affect the semantics and semiotics of the oath as a source of judicial ethics and professional conduct. The oath of the magistrate was taken at the first inauguration before the General Assembly of the Court. In the event of refusal to take an oath, the person shall be deemed to not take office. Thus, the entry into office of a magistrate has a complex factual composition, the final and decisive legal fact of which is to be sworn in. Not taking an oath was regarded as a lack of a positive procedural requirement for the status of a magistrate, which has existed in Bulgarian law since 1899. This historical period preceded the secularisation of justice from Christian dogmas, the separation of religious from secular (characteristic of the Enlightenment epoch), since it is apparent from the content of the oath that the judge took it before the King of the Principality and before God, assuming that during the Renaissance, the legislator decided that the name of God should be present in the oath of judges and prosecutors. The Bulgarian legislator wanted to consolidate the secular laws with the authority of religion and to make a bridge between them. The oath resembled a prayer – a request to God for the judge to be fair – to receive the divine mind when judging. The later is proved by the last word “Amen.” The post-liberation magistrate followed Solomon’s example and the judicial achievements of the Anglo-Saxon system at his inauguration – seeking wisdom and making requests to God. On the other hand, the oath contained concepts such as honor, integrity, independence, impartiality, decency, which are universal for today`s world, as described in the Bangalore Principles from 2001. This is a sign of the progressive spirit of the post-liberation Bulgarian and his desire to prove and show that the restored Bulgarian administration of justice has a place on the European judicial scene. These ideals and values, adopted by the legislator, set basic standards of the justice in Bulgaria, which are close to the European ones. Objectively, even then, the Bulgarian magistrate was enlightened with values, covered standards that were codified in various international treaties much later.

Oath 1934

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

XIVa. Of the oath

(New chapter: From August 16, 1935).

Article 121a. Any judge or prosecutor on taking office shall take the following oath:

“I promise, and swear, in the Name of Almighty God, to be faithful to His Majesty the King of Bulgarians, to perform holy and inviolable laws of the Kingdom, to judge by a pure conscience, without every bias and personality, to keep holy the mystery of the counseling and to act in every way as an honest, good and just judge, remembering that I will give account of all things to the law and to God.” Amin’

Article 121b. Notaries, registrars, bailiffs and candidates for judicial office on inauguration take the following oath:

I swore by the Name of Almighty God, to be faithful to His Majesty the King of the Bulgarians, to keep holy and inviolable the laws of the kingdom, to perform honestly and conscientiously the duties of the service entrusted to me, and all the rules, orders and orders which relate to these duties, do not exceed my authority, which has been given to me and do not intentionally cause harm and loss, to keep secrets of the deeds which are entrusted to me and ordered to perform in the circle of my duties, remembering that I am obliged to give account of all things before the law and before God. Amin.

Article 121c. The officials listed in the preceding articles shall be sworn in by the priest before the general meeting of the court to which they are appointed.

Article 121d. If the appointed official of the judicial office refuses to take the oath established above, he shall be deemed not to have accepted the post.

NOTES:

The oath of 1934 began to apply only from 1935, when the Act was promulgated (SG No 83 16.8.1935) to the law introducing new provisions on the oath. The oath was taken by a judge and prosecutor at the initial inauguration before the general meeting of the court in which the person will work, but through a priest. Its application was part of the factual composition of that post. A different oath was taken by notaries, clerks, bailiffs and candidates for judicial office. The oath was no different in meaning and content from that of 1899. The only change was grammatical due to the reform of the Bulgarian literary language.

Oath of judges 1948

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Art.23. Each judge upon taking office shall take the following oath before the General Assembly of the Court:

“I swore on behalf of the people to be faithful to the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, to enforce the laws of the country, to judge in a clear conscience without bias, to keep the secrets of the meetings and to act in everything as a just judge, and I swore.”

Judicial candidates, additional members, district judges and deputies shall take an oath before the general meeting of the relevant regional court.

The same oath is taken before the district judge before the President of the Court and the jurors respectively before they begin to perform their duties.

The other officials of the judicial office shall take the oath provided for in the Civil Servants Act.

NOTES:

On 26 March 1948, SG No 70 was promulgated, in which the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act 1948 and the People’s Courts Act 1948 were promulgated. These laws repealed the Court Order Act of 1934. This was the year in which the judicial professions of magistrates, on the one hand, and prosecutorial and investigative professions, on the other, were first divided. There were two statutes, according to which the prosecutor’s office and the investigating office were to be sworn in other than the judge’s office.

When comparing the contents of the 1948 judicial oath with that of 1934, it is established that the main difference is the implementation of justice in the name of the Bulgarian people, not of God and the King. This fact is a natural move by the changes in political life in a country, given the idea of the capture of power by the “people – the proletariat” and the abolished monarchy as a constitutional form of government of the state. This oath lacked the verb “promise”, which was replaced by “swear”, in which semantic meaning there was no great difference. The oath of the judge did not end with the sacred word “Amen”, but with “I swore.” Faith in religion was replaced by faith in and promise to the people – the totality of mass, people, the interests of the group, which was characteristic of Marxism. The vocabulary is evidence of the changed socio-economic relations and the views of Marxism as a philosophical atheistic current. The content of the oath also determines the type of government in the country. If in 1935 the judges swore in the name of the king, i.e. monarchy as a form of government, in 1948 the judges swore in the name of a republic, by a totalitarian regime. However, the categories of observance of the laws of the country, good conscience, impartiality, secret of deliberation, justice were preserved and reproduced in the 1948 oath, which is evidence that, despite the changed political situation, justice relied on the same values of 1935, now known as the Bangalore Principles.

Oath of prosecutors 1948

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Art.24. On taking office, prosecutors and investigators shall take the following oath:

“I swore in the name of the people to be faithful to the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, to preserve the state and public order established by the Constitution and the legality of the country, and to perform my duties conscientiously. I swore to you.

The Prosecutor General of the Republic shall take this oath before the Presidium of the National Assembly, the other prosecutors before the prosecutor immediately above, and the investigators before the district prosecutor.

All other officials at the Prosecutor’s Office and the investigators shall take an oath under the Civil Servants Act.

NOTES:

On 26 March 1948, SG No 70 was promulgated, in which the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act 1948 and the People’s Courts Act 1948 were promulgated. These laws repealed the Court Order Act of 1934. This was the year in which the judicial professions of magistrates, on the one hand, and prosecutorial and investigative professions, on the other, were first divided. There were two statutes, according to which the prosecutor’s office and the investigating office were to be sworn in other than the judge’s office.

The difference between the 1948 prosecutor’s oath and that of 1935 lies down to the difference between the judicial oaths of those two years. According to the 1948 Act, the Prosecutor General took an oath before the Presidium of the National Assembly, the other prosecutors before the immediately higher degree prosecutor and the investigators before the district prosecutor. The difference between the judicial and prosecutorial oaths of 1948 is that prosecutors and investigators swear to preserve the established state and public order, which was lacking in the judges’ ones. The judge was under an obligation to comply with the laws and the prosecutors and investigators to maintain the established state order. The later shows that at that time the prosecution and the investigation were more functionally connected with the executive power, as they defended the form of government. It is not a surprise that in the oath for attorneys the prosecutor and the investigator must conscientiously carry out their “duty”. The legal semantics of “duty” refers to executive bodies as a place in the state apparatus rather than to the judiciary. The judge’s oath used the word “judge” but not “duty”. In this sense, the Prosecutor’s Office seemed to be the pillar of the form of state power and its servitor. However, in the history of the oath of the magistrate, a new ethical principle has emerged, namely the “conscientious execution” of the prosecutor’s office, which is fully in line with the principle of adherence to the Bangalore Act.

Oath of judges 1952

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Art. 30. Each judge, upon taking office, makes the following promise before the General Assembly of the Court.

“I promise to the people to be faithful to the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, to execute and enforce the laws accurately, to judge in a clear conscience and without bias, to keep the secret of meetings and to be a just judge.”

The People’s Judges make a promise before the General Assembly of the District Court.

The same promise is made to the People’s Judge, respectively to the President of the Court, and to the jurors before they begin to perform their duties.

Judges and jurors in military courts make the above promise with the following addition:

“I also promise with all my actions to protect the power, discipline and order established in the Bulgarian People’s Army and the independence of the homeland.”

БЕЛЕЖКИ:

On 7.11.1952, in issue 92 of the State Gazette, the new statutes were published – the Law on the Structure of Courts 1952 and the Law on the Prosecutor’s Office of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria 1952, which respectively repealed the laws of 1948. The profession of military judge was introduced, but the one for a military prosecutor.

The oath of 1952 was the same for judges and jurors, which is evidence of the equal weight of the judges’ votes in the delivery of judgments and the conditionality of the administration of justice to the socio-economic conditions relevant for socialism. The magistrate’s oath no longer ended with the sacred word “I swore.” There was no final word in the oath, which created a feeling of incompleteness of what was said. There were two different oaths, depending on the authority in which the magistrate was adjudicated – ordinary or military court. Since 1952, the legislature has made a difference in the administration of justice between an ordinary judge and a military judge. Every soldier has taken a military oath, the violation of which is an independent composition of a violation of a law. Under Article 30(5) of the 1952 ZUS, military judges and jurors made the same promise as ordinary judges, with the following addition: “I also promise with all my actions to protect the power, discipline and order established in the Bulgarian People’s Army and the independence of the homeland”.

Oath of prosecutors 1952

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Art.15. Prosecutors and investigators on taking office make the following promise:

“In the name of the people, I promise to be faithful to the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, to preserve the state and public order established by the Constitution, to watch over the observance of legality in the country and to perform my duties conscientiously.”

The Prosecutor General of the People’s Republic makes this promise to the Presidium of the National Assembly, and all other prosecutors and investigators – to the directly above-ranking prosecutor.

NOTES;

On 7.11.1952, in issue 92 of the State Gazette, the new statutes were published – the Law on the Structure of Courts 1952 and the Law on the Prosecutor’s Office of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria 1952, which respectively repealed the laws of 1948. The profession of military judge was introduced, but the one for a military prosecutor.

The Prosecution and Investigative Oaths of 1952 differ mainly in two regards compared to the 1948 oath. Firstly, the verb ‘Swear’ was replaced by ‘I Promise’, in the semantic sense of which there is little difference. Second, the oath, like the one for judges, did not end with “I swore” and therefore again created a sense of incompleteness of the promise. For the rest of the content, the oath reproduced the text of the 1948 oath.

Oath of prosecutors 1960

NOTES:

The Public Prosecutor’s Office Act 1960 repealed the 1952 Act. That law does not contain provisions on taking an oath on entering office, before whom it is due and what its content is. According to Article 62 of the Act, the internal order of the Prosecutor’s Office is to be determined by the Rules of the Prosecutor’s Office of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria. After consulting the SG and a bibliographic report, it was CITATION Йол88 l 1026 (Yolova & Kiskinova, Legislation of the People's Republic of Bulgaria 1944 - 1986. Reference book, 1988) CITATION Йол82

l 1026 (Yolova & Kiskinova, Reference book on the legislation of the People's Republic of Bulgaria 1944 - 1981., 1982) CITATION Нак82 l 1026 (Criminal and structural laws, 1982) CITATION Пав79

l 1026 (Pavlov, 1979) found that for the period 1960 to 1971 there was no promulgated Public Prosecutor’s Office Rules for the IDR 1960. At the same time, the TFP of the 1981 Public Prosecutor’s Office Regulations stated that the Rules repealed the 1968 Public Prosecutor’s Office Regulations. The lack of publication was most likely due to the political situation of the said period, so that the Rules were most likely intended for internal use and could not be published.

Oath of judges 1976

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Law on the Settlement of Courts: Article 77. (1) The judges and the jury shall be sworn in.

(2) The oath shall be taken before the President of the relevant court. The President of the Court shall take an oath before the President of the Higher Court. The President of the Supreme Court is sworn in before the National Assembly.

Rules governing the organisation of the abots of district, regional and military courts: Article 14. (1) Judges and jurors of the district and district courts shall, before they begin their duties, take the following oath: I swore to the Bulgarian people to carry out my activities in accordance with the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, to execute and enforce the laws accurately, to judge by internal conviction and impartiality, to be a just judge, to keep the secret of meetings and to observe the rules of socialist morality impeccably. I swore.

(2) Judges and jurors of military courts shall take the oath referred to in the preceding paragraph, with the following addition: I swear with all my actions to protect the power, discipline and order established in the Armed Forces of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria and the independence of the homeland.

(3) For the oath, the judges and the jury sign a sworn list.

NOTES:

The Court Devices Act 1976, which repealed the 1952 ZUS, lacked an oath on the part of judges. Article 77 of the Act states only that judges and jurors are sworn in before the president of the relevant court and the presidents – before the higher court. It was not specified whether the oath was only for initial appointment or also in cases of transfer and promotion. The oath of magistrates itself was contained in Article 14 of the Rules governing the organisation of the work of regional, regional and military courts (promulgated in SG No 89 of 15.11.1977). That approach casts doubt that the legislature did not hold the oath as a source of judicial ethics and professional conduct, since it was not in the law governing primary public relations in a regulatory act. It is obvious that its understanding for the oath is that it is with a subsidiary nature and is therefore governed by a regulatory act. The trend continued that the oath was the same for judges and jurors in view of their voting weight. There were two different oaths depending on the authority in which the magistrate was adjudicated – ordinary or military court. Thus, the legislature continued to make a distinction in the administration of justice between an ordinary judge and a military judge.

Comparing the contents of the 1976 Judge’s oath with the previous ones, it was found that the judges swore to observe socialist morality. The existence of this philosophical category was a natural result of changes in political life in the country. Faith in religion was replaced by a new kind of morality, namely socialist morality, in which the judge swore to observe. It was a category known only in the former Eastern Bloc countries, adopted by Engels’ views and was taken up by communist leaders. It can therefore be concluded that at this stage in the history of our country, the fear of the violation of God’s laws has been eliminated. For the fear of being under the public scrutiny the magistrate declared respect for the value of public morality. In fact, it was formed politically to serve the interests of the totalitarian state. The oath contained a promise to implement the Constitution and the laws of the Republic, consistent with established tradition. The principles such as internal conviction, impartiality, justice, the secret of the meeting, which constitute the historical achievements of the Bulgarian jurisprudence, continued to have binding application in the administration of justice. It is apparent from the analysis of the oath of military judges that they had different treatment on the part of the lawmaker. Instead of “I swear,” the military judges used the synonymous phrase “I swear” but did not promise to observe the laws of the Republic. However they would guard the power, discipline and order established in the Armed Forces of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria and the independence of the homeland. In fact, during the years of the evolving socialist society, the question of the independence, objectivity and fairness of the administration of justice was not really raised, no indexes of law enforcement and public trust in the judiciary were measured.

Oath of prosecutors 1980

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Article 48. (1) The Military Prosecutor’s Office shall supervise the exact and uniform implementation of the laws in the system of the Ministry of People’s Defense, the Ministry of Interior, the Construction and Transport Forces and other agencies provided by the law.

(2) The military prosecutor’s office shall organise and combat crimes and other offences and shall exercise the powers provided for in this Act in the departments and troops referred to in paragraph 1.

(3) With all its activities, the Military Prosecution Service promotes the education of the servicemen in a spirit of accurate and consistent implementation of the laws, the military oath,the military statutes and the orders of the commanders.

NOTES:

In the Act on Prosecution of 1980, the only text dedicated to the oath is that military prosecutors took an oath (Article 48(3)). Pursuant to § 2 of the Transitional and Final Provisions of the Act, a Rules for its Application by the Prosecutor General have been issued for the application of this Act. Those regulations were promulgated in SG No 56 of 17 July 1981, but there were also no provisions relating to the taking of the oath – procedure, order and content. Therefore, during the period considered (since 1980. until 1994), the oath of prosecutors and investigators was not essential to have a place in the text of the law and the regulatory act.

Oath 1994

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Article 107. Each judge shall, upon first taking up office, take the following oath: I swear in the name of the people to observe precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties according to conscience and inner conviction, to be impartial, objective and just, to contribute to raising the prestige of the profession, to keep the secret of the meeting, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 108. Each prosecutor and investigator shall take the following oath upon initial taking up office: I swear in the name of the people to observe precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties according to conscience and inner conviction, to be impartial, objective and just, to contribute to raising the prestige of the profession, to keep the official secret, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 109. (Am. — SG No 104 of 1996, amended. — SG No 43/2005, in force as of 1.9.2005) Each State bailiff and registry judge shall take the following oath: I swear in the name of the people to observe precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties honestly and in good faith, to keep the secret of my affairs entrusted to me, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 110. (1) (Am. — SG No 74/2002) The oath shall be held before the judges, prosecutors and investigators of the relevant judicial authority. After taking the oath, a sworn list is signed.

(2) Persons who refuse to take an oath may not take office.

Initial version of Art.109: Each bailiff and notary shall, upon first taking up office, take the following oath:

I swear in the name of the people to observe precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties honestly and in good faith, to keep the secret of my affairs entrusted to me, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Initial version of Art.110: The oath shall be taken before the judges, prosecutors and investigators of the respective district court. After taking the oath, a sworn list is signed.

(2) Persons who have refused to take an oath may not take office.

NOTES:

With the changes in 1989 and the adoption of the Judicial System Act 1994 (prom. SG No 59 of 22.7.1994) the structure of the judiciary has radically changed. First, judges and prosecutors take a different oath as magistrates, which is an independent expression of the separation of those two professions as separate branches of the judiciary. A significant difference is that the statutory provisions governing the procedure for taking an oath are laid down in the law and not in a regulatory act. This is evidence that the legislature placed great importance in the magistracy’s oath as a source of ethics, as opposed to the previous statute, in which the oath was laid down in a regulation. The oath is declared at first taking office before the judges, prosecutors and investigators of the relevant judicial authority and is an element of the taking position. The oath of judges and prosecutors differed from that taken by state bailiffs and registry judges. The content resembled the original content of the oath of 1899, but there were significant differences. The oath was in the name of the people and the Constitution. The modern magistrate judged only by the will of the law and evidence. The difference between the oaths of the judge, the prosecutors’ ones and the investigators’ ones lies in the fact that, in making decisions, the judge took part in a meeting which had to be kept secret and that prosecutors and investigators had access to information which they had to retain. The oaths of the magistrates were only formally different. For that period, there was also no separate oath for a military judge and a military prosecutor, so it could be concluded that they were taking the same oath as the other magistrates.

Oath 2007

EXTRACT FROM THE LAW:

Article 155. Each judge shall, upon first taking up office, take the following oath: “I swear in the name of the people to implement precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties according to conscience and inner conviction, to be impartial, objective and just, to contribute to raising the prestige of the profession, to keep the secret of the meeting, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 156. Each prosecutor and investigator shall take the following oath upon initial taking up office: “I swear in the name of the people to implement precisely the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, to perform my duties according to conscience and inner conviction, to be impartial, objective and just, to contribute to the promotion of the prestige of the profession, to keep the official secret, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 157. (1) The oath shall be held before the judges, prosecutors and investigators of the respective judicial authority.

(2) After taking the oath, a sworn list is signed.

Article 158. Each State bailiff and registry judge shall sign an oath sheet with the following oath: I swear, in the name of the people, to apply the Constitution and the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria precisely, to perform my duties honestly and in good faith, to keep the secret of my affairs entrusted to me, always remembering that I am responsible for everything before the law. I swore!

Article 159. A person who refuses to take an oath or sign a sworn list may not take office.

NOTES:

The oath of 2007 (published. SG No 64 of 7 August 2007) is different in content for judges, prosecutors and investigators. This is due to the fact that for taking up office before the judges, prosecutors and investigators of the relevant judicial body, and the magistrate should sign a sworn list. That is to say, the composition of the inauguration is complicated, and in order to fulfil the whole, the following cumulative conditions must be met – taking an oath and signing a sworn list. The mere realisation of one of the two legal facts is not sufficient for the legal relationship to be regarded as having arisen (Article 159 of the JSA). The oath of a state bailiff and registry judge is different from that of magistrates. With regard to the text and content of the oaths, there has been no change with the oath of 1994, which is why the above applies here as well.

CONCLUSION

The Magistracy’s oath has existed in every period of the social development of our state – from the Liberation of 1878 to the present day. Examining its historical course, it is established that the magistrate’s oath contains traces of the socio-political attitudes and cultural understandings of society about the role of the magistrate during different times, therefore the oath can be qualified as a direct written evidence of the development of the history of the Bulgarian state and the law and rule of law. Oath is the fingerprint in which are encoded understandings of profession, ethics, morality, their observance and manifestations in practice. Despite its short period since its establishment, the magistrates’ oath reproduces and raises on a pedestal those universal Bangalore principles such as independence, justice, integrity, which are the moral compass of the Bulgarian magistrate. Like the Hippocratic Oath, the Magistracy Oath also represents a promise and an ethical view in the judiciary. Knowledge of the oath is therefore very important for the development of the magistrates’ profession and of the ethical principles to which it should be subject.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Braykov, V. (2014, 12 24). TEMPLE WITHOUT GOD (notes on Bulgarian democracy). From Braikov’s web site: https://www.braykov.com

Criminal and structural laws. (1982). Sofia: Science and Art.

M., G. (2016, 09 27). Organization of the judiciary in Bulgaria in the period 1878-1941. From sadebnopravo: http://www.sadebnopravo.bg/biblioteka/2016/9/27/-1878-1941-

Maximov, Х. (1957). Reference book on the legislation of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria 09.09.1944 – 30.06.1957. Sofia: Science and Art.

Pavlov, S. (1979). Criminal process of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria. Sofia: Science and Art.

UNODC. (2018). Judicial Conduct And Ethics Trainers’ Manual United Nations, Vienna, 2018. Vienna: UNITED NATIONS.

Yochev, E. (2016, 3 2). 135 years since the adoption of the first Bulgarian Law on the Organization of the Courts. From sadebnopravo: http://www.sadebnopravo.bg/biblioteka/2016/3/2/135-

Yochev, E. (2016, 01 18). A few words about the Laws on the Organization of Courts, Judicial Districts and the Territorial Location of Courts in Bulgaria (1878-1944). From sadebnopravo: http://www.sadebnopravo.bg/biblioteka/2016/1/18/-1878-1944-

Yolova, G., & Kiskinova, L. (1982). Reference book on the legislation of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria 1944 – 1981. Sofia: Science and Art.

Yolova, G., & Kiskinova, L. (1988). Legislation of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria 1944 – 1986. Reference book. Sofia: Science and Art.

NOTES

[1] Jeremy Cooper is a law professor at the Southampton Institute, was a court judge for people with mental problems, director of the Institute for the Training of Magistrates in London and lecturer at EJTN. He has published books on Judicial Ethics and Professional Behaviour at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.